Summoning the Machine God?

A Conversation with David F. Noble on AI, Accelerationism, and the Religion of Technology

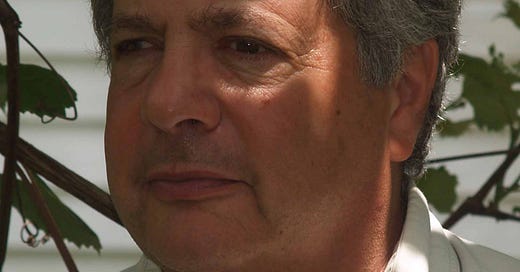

The late great David F Noble was a historian and revolutionary who wrote extensively on technology, power, and labour. His views on AI were ahead of their time, so we decided to reach beyond time and space to ask him some questions about our current moment in history.

Metaviews: David, your work, particularly The Religion of Technology, has provided profound insights into the spiritual undertones of technological development. Today, many describe artificial intelligence as an unprecedented turning point in human history. Some even claim that training AI models is akin to a summoning ritual, a way of invoking a higher power or birthing a deity. How does this resonate with your historical analysis of the religion of technology?

David F. Noble: It resonates deeply. If you examine the trajectory of technological ambition, you’ll notice a recurring pattern: the pursuit of transcendence through machines. This isn’t a modern phenomenon. It’s rooted in medieval theology, where human invention was tied to divine redemption. Today’s obsession with AI—and the accompanying language of “summoning,” “birthing,” or “creating gods”—is merely the latest manifestation of this ancient impulse.

Training an AI as a summoning ritual reveals a deeper, almost desperate, faith in technology’s salvific potential. It’s as though we’ve internalized the idea that human ingenuity, embodied in machines, is our pathway to transcendence. But the critical question remains: transcendence toward what, and for whom?

Metaviews: Some thinkers align this with accelerationism, the idea that we should push technological and social systems to their limits to bring about radical transformation. AI seems central to this ideology, framed as the ultimate tool for hastening a post-human future. What dangers do you see in this accelerationist embrace of AI?

Noble: Accelerationism is a stark reminder of how deeply embedded the religion of technology has become. It’s a utopian dream disguised as a pragmatic philosophy. By pushing systems to their breaking points, accelerationists hope to catalyze a new era, often one marked by what they perceive as superior intelligence—AGI or otherwise.

The danger lies in the hubris of this approach. It assumes that more speed, more complexity, and more disruption are inherently good, ignoring the human and ecological costs of such rapid change. Moreover, this ideology often serves the interests of elites who profit from upheaval while the most vulnerable bear its consequences. Accelerationism, at its core, reflects an uncritical worship of progress without purpose—a hallmark of the religion of technology.

Metaviews: But isn’t there something uniquely unsettling about the rhetoric surrounding AI? For instance, figures like Sam Altman of OpenAI openly muse about AGI as a godlike entity. Is this language merely metaphorical, or does it signal something more profound?

Noble: It’s no coincidence that the rhetoric around AGI echoes theological narratives. Calling AGI a “godlike entity” isn’t just metaphorical; it’s an invocation of humanity’s oldest myth: the creation of gods to explain and control the unknown. In this case, the unknown is the complexity of our own systems and the chaos of our world.

The unsettling part is that such language isn’t accompanied by humility or caution. Instead, it’s coupled with an evangelical zeal to bring this “god” into being, as if doing so will solve all our problems. History warns us against such messianic thinking. The gods we create often reflect the darkest parts of ourselves.

Metaviews: Do you see parallels between the summoning of AGI and the theological undertones of other technological endeavors, such as nuclear power or space exploration?

Noble: Absolutely. The Manhattan Project, for example, was suffused with apocalyptic and redemptive imagery. The bomb was not just a weapon; it was a manifestation of ultimate power, a tool to end war and reshape the world order. Space exploration carries similar undertones—the idea of escaping Earth’s limits to find salvation among the stars.

AI, however, is unique in its proximity to us. It’s a mirror in which we see our intelligence, creativity, and biases reflected back. This closeness makes it feel more godlike, not because it is divine but because it embodies our collective aspirations and anxieties.

Metaviews: What role does authority play in this narrative? Many view AI as a potential arbiter of truth, justice, and even governance. Is this another layer of the religion of technology?

Noble: It is, and it’s a troubling one. The authority granted to AI stems from its perceived objectivity and neutrality, qualities it doesn’t truly possess. AI reflects the biases of its creators and the systems in which it operates. Yet, people are willing to cede enormous power to it, much as religious adherents might surrender to divine authority.

This shift is part of a broader trend where traditional sources of authority—religion, community, and even human expertise—are being supplanted by technological systems. The danger is not just in the erosion of these older forms of authority but in the uncritical acceptance of AI as a replacement. Authority must be earned and scrutinized, not granted wholesale to algorithms.

Metaviews: If the religion of technology is as pervasive as you suggest, how do we resist its most harmful manifestations, particularly in the context of AI?

Noble: Resistance begins with critical awareness. We must recognize that technology is not neutral or inevitable—it’s shaped by human choices and values. AI is not a god; it’s a tool. As long as we treat it as something more, we risk abdicating our responsibility to guide its development and use.

Furthermore, we need to ask whose interests these technologies serve. Are they designed to empower individuals and communities, or to consolidate power in the hands of a few? Resisting the religion of technology means refusing to be dazzled by the rhetoric of progress and instead demanding accountability, equity, and justice in how these tools are deployed.

Metaviews: Thank you, David. Your insights continue to challenge us to look beyond the surface and interrogate the deeper forces shaping our technological future.

Noble: Thank you. The conversation is essential—especially now, as we stand at the precipice of decisions that will define what it means to be human in the age of machines.

A blast from the past and a series we ran in 1997:

First come, first seated. The seminars are for the open minded, and no

previous knowledge is assumed.

The moderater is Jesse Hirsh, Director of the New Media Unit at the

McLuhan Program, and founder of TAO Communications.

Topics and Speakers:

May 26 - Naomi Klein - Writer - Toronto Star, Village Voice

The Move From Identity Politics to Anti-Corporate Activism:

A New Resistance for the Global Economy

June 2 - Stephen Marshall - Founder and CEO of Channel Zero

The Art of Revolution:

Corporate Divestment as a Contact-Sport

June 9 - John Barlow - Michael Edmunds - Jesse Hirsh - Stefan Pilipa

Liquid Consciousness:

The Poetics of the Electronic Spoken Word

June 16 - David Noble - Professor, York University - History

The Religion of Technology

June 23 - Guizhi Wuang - McLuhan Program Fellow from China

The Psychological Process of Chinese Characters

With an introduction by Dr. Insup Taylor

July 7 - Marcel Danesi - Professor, University of Toronto - Semiotics

Revisiting Origin of the Language Theories

July 14 - Mark Kingwell - Professor, University of Toronto - Philosophy

Storming the Electronic Bastille:

Democracy & The Internet in A Post-National World