Donald Trump’s latest threats to eject Canada from the Five Eyes alliance should come as no surprise. The president has already demonstrated his willingness to shatter longstanding diplomatic and security relationships in pursuit of his personal and political goals. What is surprising, however, is the assumption that Canada’s participation in the alliance is still relevant at all. The Five Eyes, once a powerful intelligence-sharing network, has been mortally wounded—not just by Trump’s erratic foreign policy, but by the shifting realities of global power and technology.

To understand why the Five Eyes is collapsing, one must first understand its true purpose. While often framed as a straightforward intelligence-sharing partnership, the alliance has historically served two primary functions:

Evading Domestic Legal Restrictions – The most critical function of the Five Eyes was to allow member states to bypass domestic laws that limited intelligence operations. Intelligence agencies in Canada, the U.S., the U.K., Australia, and New Zealand historically faced restrictions against spying on their own citizens. The workaround? Have a friendly partner spy on your people for you. The alliance ensured that intelligence could be gathered under the guise of international cooperation, allowing governments to maintain plausible deniability while still accessing data on their own populations.

A Shared Buying Group for Technology and Infrastructure – Intelligence is expensive, and pooling resources has long been a way for smaller partners to access cutting-edge surveillance tools they could not afford on their own. The U.S. benefited immensely, as its allies were effectively subsidizing American technological dominance by purchasing their systems. At the same time, the other Four Eyes benefited by gaining access to infrastructure they otherwise wouldn’t have been able to build independently.

Both of these core functions have now been rendered obsolete. The U.S. has largely abandoned any pretense of legal constraints on domestic surveillance, meaning it no longer needs foreign intermediaries to collect data on its own citizens. Simultaneously, the American security apparatus has little incentive to share its most valuable technological and operational advantages with allies, especially ones it no longer sees as strategically vital. The Trump administration’s hostility toward Canada is not an anomaly—it is an extension of a broader trend in U.S. foreign policy that views allies as disposable assets rather than partners.

The logical response for Canada, as well as the U.K., Australia, and New Zealand, would be to disengage from intelligence sharing with the U.S. However, this is not as simple as a policy decision. The hard reality is that these nations' security infrastructures have been deeply intertwined with American systems for decades. The extent to which their communications, data networks, and intelligence agencies have been compromised by U.S. influence remains an open question. In a world where the United States assumes it no longer needs its allies, the reverse assumption must also hold: Canada and the others must assume that their own intelligence networks have already been infiltrated and rendered vulnerable.

So, what comes next? The end of the Five Eyes does not mean the end of intelligence collaboration altogether. In fact, this moment provides an opportunity for a fundamental rethink of what intelligence-sharing should look like in an era of decentralized threats and emerging multipolarity. A more regionally focused intelligence consortium, one that prioritizes actual mutual benefit rather than dependency on Washington, could emerge. Canada and its former Five Eyes partners might find stronger partnerships in Europe, Asia, or even the Global South—nations that also have reason to be wary of U.S. dominance and who might be interested in cooperative security models that do not rely on a singular superpower’s benevolence.

Another possibility is the emergence of an open-source intelligence agency operated by and for citizens. With surveillance technology increasingly accessible, a decentralized network of independent analysts, journalists, and technologists could work together to track government overreach, expose corruption, and counter disinformation. Such an agency could serve as a check on rising authoritarianism, ensuring that intelligence gathering is used to empower the public rather than control it. By leveraging open-source tools, cryptographic protections, and decentralized coordination, a citizen-driven intelligence network could create a counterweight to both state and corporate surveillance regimes.

The age of the Five Eyes is over. What remains to be seen is whether its former members will adapt to this new reality or continue to operate under the illusion that they are still on the inside of an intelligence club that no longer truly exists.

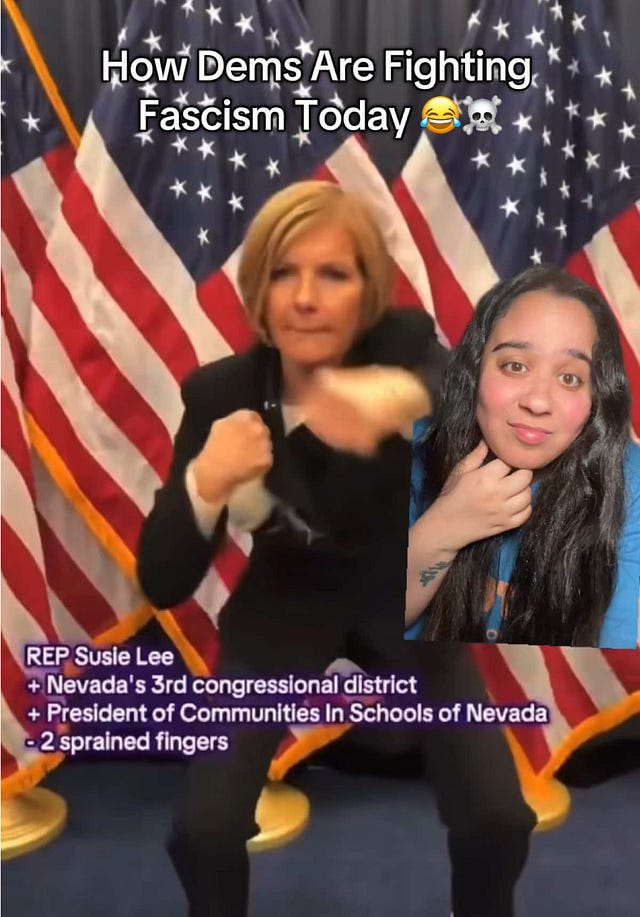

Tiktok failed to load.

Tiktok failed to load.Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser